|

|

The Lafayette

Street Bridge -

Part 3 of 4 |

|

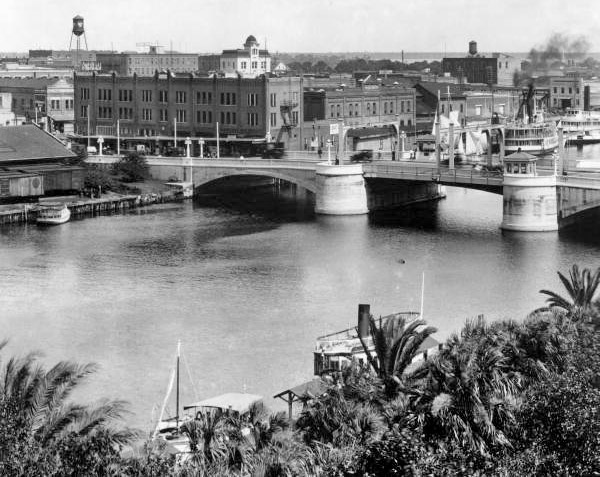

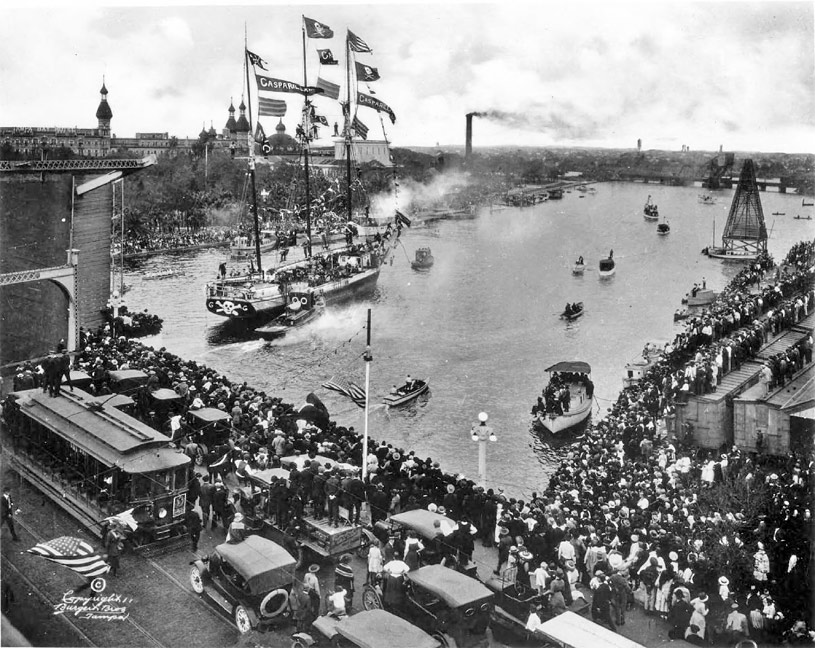

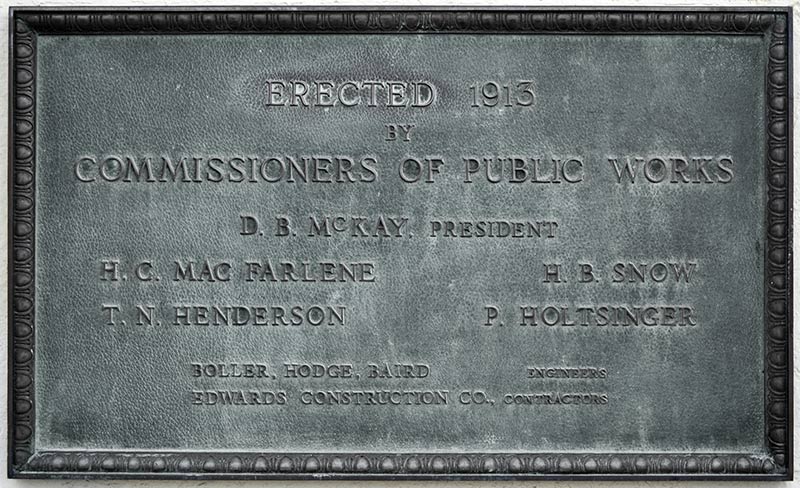

| The Third Lafayette Street Bridge | |

|

|

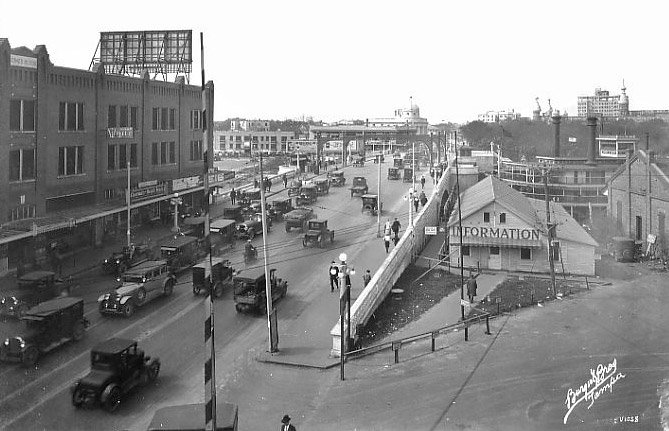

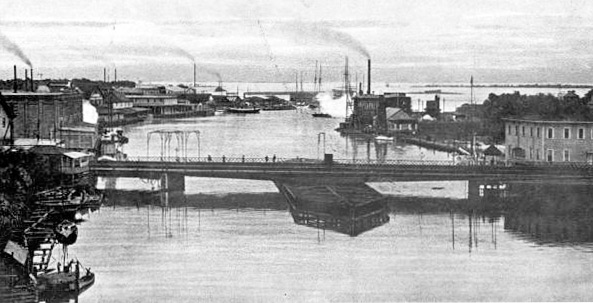

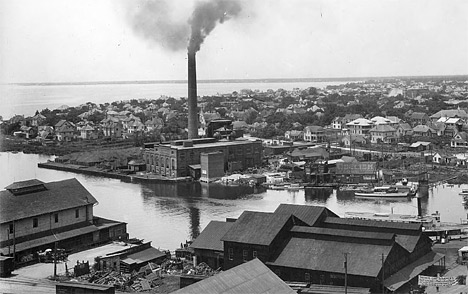

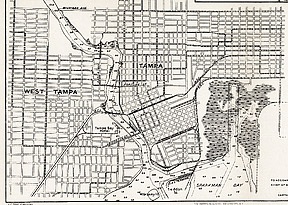

By the turn of

the century, nearly 16,000 people called Tampa home, and the Lafayette

Street Bridge did not meet the needs of such a rapidly growing city.

Bonds Approved for City Improvements |

|

In 1907, progressive Tampans were

optimistic that a b

|

|

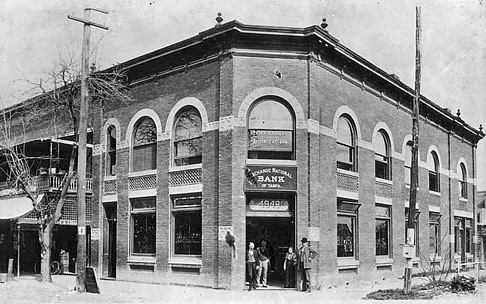

William Frecker had been successful in his quest for mayor in 1906, defeating Frank Bowyer and Arthur Cuscaden, a businessman who had served on the City Council during the McKay administration. A new bridge over the river at Lafayette Street was to be paid for by these bonds. In November 1907 the city council passed an ordinance approving bonds (subject to voter approval) to pay for a new Lafayette Street Bridge, curbing and paving, sewers, a city hospital, a city stockade, and to pay the remaining debt from construction of the city’s crematory (trash incinerator). |

|

ond

issue would finally pass. The city and its economy were growing, so

ond

issue would finally pass. The city and its economy were growing, so

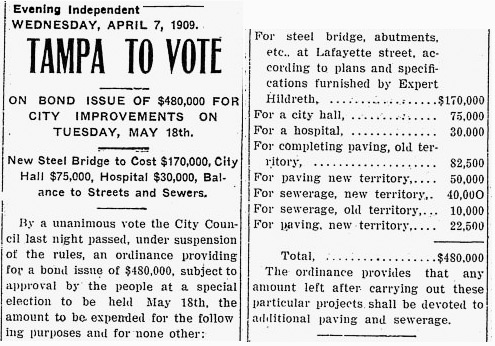

On election day May 18, 1909, turnout

was light, with 319 votes for the bonds and 830 against. In no wards were

more people for the bonds than against, even in the Third Ward, which

included Hyde Park. Tampa voters turned down the municipal bond issue that

would have paid for a new Lafayette Street Bridge, a city hall, a city

hospital, and other public improvements such as sewers and paved streets.

On election day May 18, 1909, turnout

was light, with 319 votes for the bonds and 830 against. In no wards were

more people for the bonds than against, even in the Third Ward, which

included Hyde Park. Tampa voters turned down the municipal bond issue that

would have paid for a new Lafayette Street Bridge, a city hall, a city

hospital, and other public improvements such as sewers and paved streets.

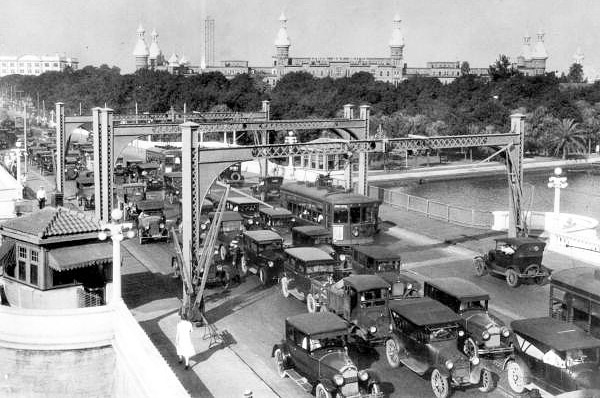

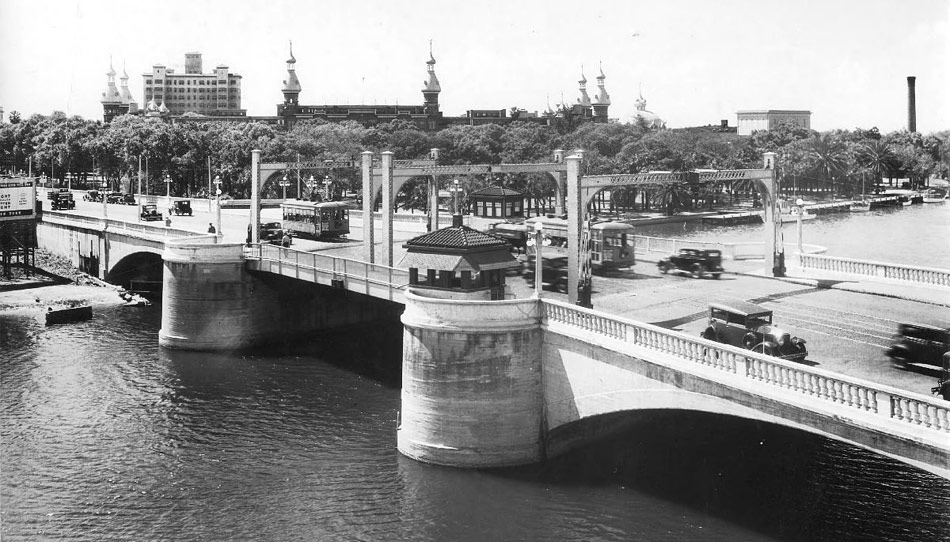

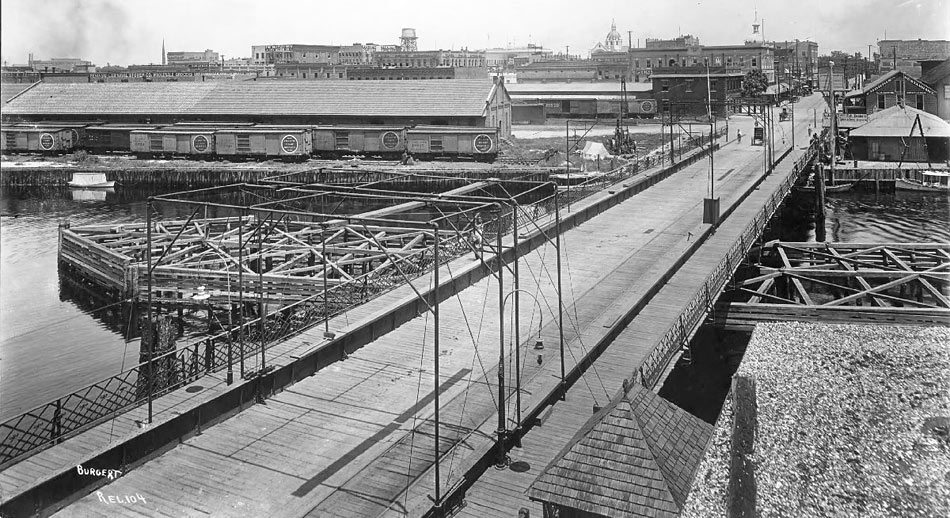

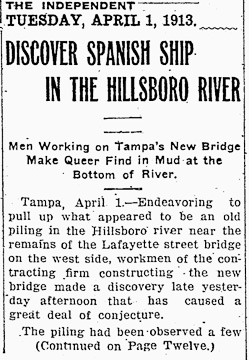

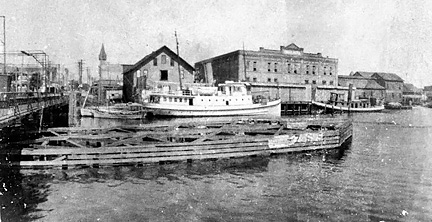

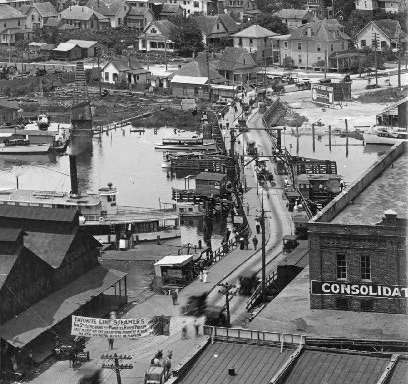

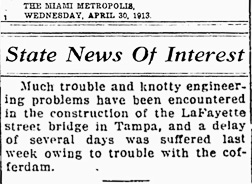

Edwards started work on the new Lafayette Street Bridge even while the old

bridge stayed opened to all traffic. Workers poured concrete walls, moved

telephone cables and electrical wires out of the way, and began driving pilings.

By early August, Edwards had forty men working on the bridge, and two times that

number later. At the southeast part of the bridge, the pile drivers encountered

what was believed to be a Spanish vessel that had “blown up” here 40 or 50 years

earlier, along with a bronze cannon.

Edwards started work on the new Lafayette Street Bridge even while the old

bridge stayed opened to all traffic. Workers poured concrete walls, moved

telephone cables and electrical wires out of the way, and began driving pilings.

By early August, Edwards had forty men working on the bridge, and two times that

number later. At the southeast part of the bridge, the pile drivers encountered

what was believed to be a Spanish vessel that had “blown up” here 40 or 50 years

earlier, along with a bronze cannon.

.jpg)