A small group of men sat around a table on which was spread out a large map of Pinellas Peninsula and surrounding country. With a pair of calipers, they carefully measured the distance by all possible routes between St. Petersburg and Tampa. “Can’t you see the answer?” asked one of the men. “Can’t you see that a bridge across Old Tampa Bay is almost indispensable? Look how much distance it would cut off. Nearly fifty miles by land-by bridge it would only be nineteen or twenty miles. Think what that would mean to this section of the state!” The others were frankly skeptical. “Sure, it would be a fine thing,” said one. “But it will never be built during our lifetime. Why it would cost millions and how could you hope to get your money back? It’s foolish to think of such a thing. Forget it.” The advocate of the bridge listened to the arguments of his friends. He heard them say how hopelessly visionary such a project was and how it could never be put through. He paid attention to all that they had to say-and then promptly disregarded their advice.

He refused to “forget” the bridge idea.

“Perhaps you gentlemen are right,” he said. “Perhaps the bridge is just a

foolish dream. But I don’t believe it. And I never will be satisfied until

the bridge is built.” |

|

||

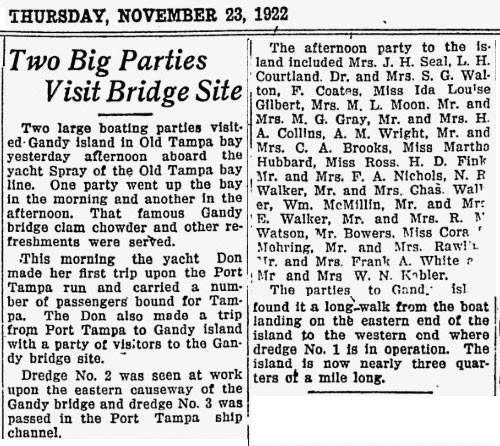

When George Gandy's colossus opened for traffic in 1924, it was the feat of its day. One of the longest toll span bridges of the world in its time, it was a financial and engineering marvel that instantly accelerated the residential and commercial development of the entire Tampa Bay area. But the major wonder of the feat was in its gestation and birth, because from the time that it was a gleam in the stern and flinty eyes of George Gandy, to the time when the first piling was hammered in to the bedrock of Tampa Bay, nearly a generation had passed. In the early 1900's, it wasn't Gandy's "colossus" but instead, his folly...a crazy notion that was greeted, at best, with patronizing guffaws from the more practical wags of the day. Over the years, the project careened on the precipice of failure enough times to make the shrewdest stock market wizard hedge his bottom dollar for lunch money and a nice, sound, U.S. savings bond. But the imposing Philadelphian simply said, "I am going to build that bridge." And with the single-mindedness of a zealot precariously mixed with a razor will and unmitigated cheek, he did. |

|||

|

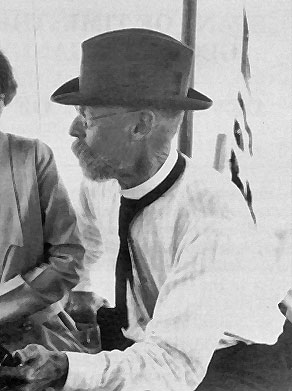

Early life & career in Philadelphia George Gandy was born in Tuckahoe, New Jersey, in 1851. He was one of two sons of sea captain Louis Gandy and Jane Reeves Gandy. George, who had an older brother named Alfred, received only a grammar school education. He grew to be 5-feet-2 and came to be called the "runt." Gandy was always defensive about his size; on many occasions he fought those who ridiculed him. When he was 16, his father went bankrupt and young George went to Philadelphia, where he studied bookkeeping for three months. At that time he lived in Northern Liberties near the home of the Henry Disston family, becoming friends with Henry's sons and having Mary (Henry's only daughter) as a playmate. When he finished bookkeeping school, Gandy went to Disston's Keystone Saw Works as a clerk in the bookkeeping department at $4 a week.

Gandy's first run-in with Disston occurred in 1872. The year found Disston stressed over a growing business and a commitment to move it to Tacony. During a discussion, he cursed at Gandy in front of the men in the office. Disston swore at him again the next morning. At the end of the workday, an annoyed Gandy headed for Henry Disston's office. Disston never stopped writing as Gandy entered the room, instead abruptly demanding, "What do you want?" Gandy waited until Disston finally looked up and raised his glasses to the top of his head. "I am only a boy and I don't think I am presuming," Gandy started, "but I have feelings of a man just the same. I don't like your treatment of me, and I want to quit." A surprised Disston replied, "But George, I didn't mean anything." Actually, Gandy liked Disston and accepted his apology. He then offered his boss some advice: "Here is your trouble. You get your mind on something and go with three or four men to see something, and when you come back to the office, five or six people are waiting to see you. Suppose when you get busy you just ring for me." Henry Disston always liked men who spoke their minds and were loyal, hardworking employees. He had found that trait in longtime family friend George Gandy. In 1872, Disston placed Gandy in charge of the payroll department. On his first day on the job, Gandy informed Disston that he would reorganize the department using his own system.

Read about the rest of George Gandy's interesting career with Disston, the improvements he made, and how things changed after his marriage to Disston's daughter and her death, as recorded by Gandy himself in his diary. |

||

|

At age 35, Gandy began suffering from a heart condition which lasted the rest of his life and was occasionally aggravated by his business dealings. In 1882, Gandy became involved in the transportation business. While working in transportation construction and operations, he achieved several prominent positions, such as secretary and treasurer of the Frankford and Southwark Railroad, vice-president of the Frankford and Southwark, president of the Omnibus Company, and president of the Fairmont Park Transportation Company. Gandy organized the construction of many trolley lines and electric railways, and was recognized in his field as an expert on traction problems. Eventually, he became vice-president of the Philadelphia Electric Traction Company. The tireless Gandy also served as president of the St. Petersburg and Gulf Railway, and this position brought him to west-central Florida in 1902.

|

|

|

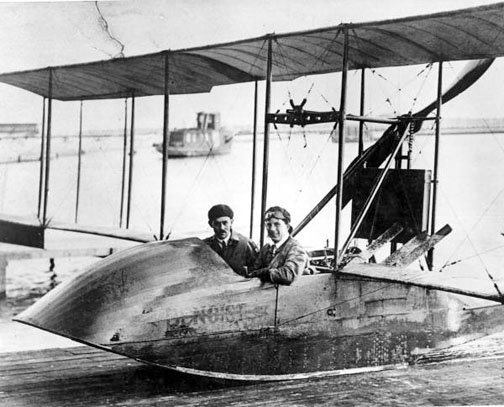

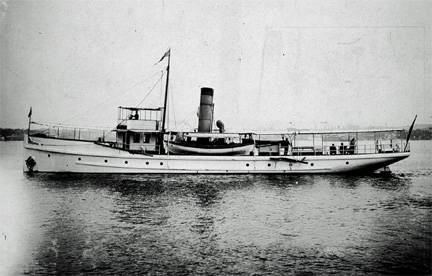

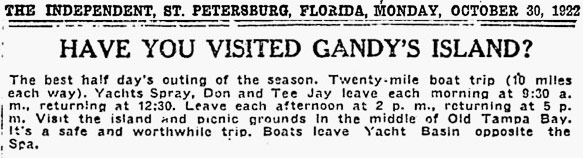

Tampa Bay Area Transit At the beginning of the twentieth century, travel between the Pinellas peninsula and the mainland of Hillsborough County was limited to difficult land routes. Despite the arrival of the railroad to the lower Pinellas in the late 1800s, journeys between Pinellas and Hillsborough remained difficult and time-consuming because no direct rail link existed until 1914. The arrival of the automobile cut the travel time, but it took approximately six hours for a model-T to make the trek around the bay on primitive Florida roads, if you didn't break down. A steamship cruise between the two cities across the bay took about two hours. In 1914, during the pioneering period of aviation, Percival Fansler's St. Petersburg-Tampa Airboat Line, with Tony Jannus in the pilot's seat, cut travel time between St. Petersburg and Tampa a mere twenty-two minutes, but this novelty quickly went out of business within 4 months. |

|

Gandy Arrives in St. Pete

On George S. Gandy's first visit to

St. Petersburg in 1902, he decided that a bridge linking St.

Petersburg with Tampa could be built across Tampa Bay at the narrowest

point. Gandy was firmly committed to completing such an ambitious

project once the population of the area had increased to a sufficient

amount so he could make large profits from tolls. In 1915 Gandy

employed a large crew of surveyors to determine the narrowest and

shallowest part of the bay. The surveys took two years to finish. Upon

completion of the surveys in 1917, Gandy secured the rights-of-way

from Pinellas and Hillsborough counties, the state, and the federal

government. The volume of permits needed today to perform such a

monumental task were not required in Gandy’s day; basically, all one

had to possess were the finances and land rights. In the 1920s,

ecological concerns were not even considered, except in very rare

cases. |

|

| With no need for environmental studies, Gandy’s project required only approval of the Florida legislature, which retained ownership of submerged land. Gandy also had to acquire permits from the War Department, since the Army Corps of Engineers had dominion over the navigable waters of the United States. The War Department also retained jurisdiction over bridges for the purpose of deploying troops in time of war or other emergencies. | |

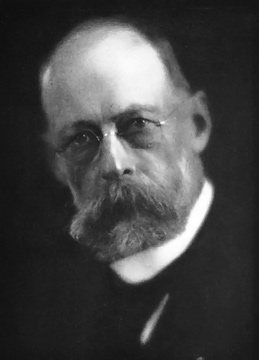

In

1909, H. Walter Fuller, president of the St. Petersburg

Transportation Co. and manager of the Florida West Coast

Co. city electric company, St. Petersburg and Gulf railway

and Johns Pass Realty Co., gave an interview to the

Independent. He expected a wave of prosperity to

sweep the country in the following year. Fuller, "one of

the live wires," was a driving force in developing the

city. He made, and lost, fortunes. Among his careers, he

was a road builder and developer (Jungle and Pasadena

subdivisions, Treasure Island). He built an electric plant

at 16th Street N and First Avenue, and helped extend

Central Avenue from Ninth Street to Boca Ciega Bay. Fuller

envisaged a bridge to Tampa, which George S. Gandy later built.

He died in North Carolina in 1942, at 74

In

1909, H. Walter Fuller, president of the St. Petersburg

Transportation Co. and manager of the Florida West Coast

Co. city electric company, St. Petersburg and Gulf railway

and Johns Pass Realty Co., gave an interview to the

Independent. He expected a wave of prosperity to

sweep the country in the following year. Fuller, "one of

the live wires," was a driving force in developing the

city. He made, and lost, fortunes. Among his careers, he

was a road builder and developer (Jungle and Pasadena

subdivisions, Treasure Island). He built an electric plant

at 16th Street N and First Avenue, and helped extend

Central Avenue from Ninth Street to Boca Ciega Bay. Fuller

envisaged a bridge to Tampa, which George S. Gandy later built.

He died in North Carolina in 1942, at 74

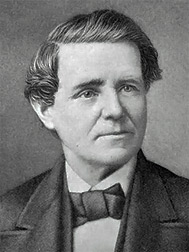

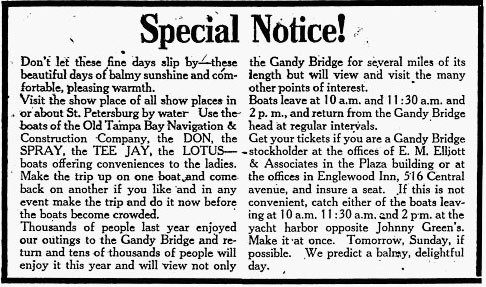

Later, convinced it was not

such a bad idea, he established the "Boulevard and Bay Land

Development Company" and scooped up some choice acreage

along the bridge approaches on Weedon Island. He offered "Five

Thousand Acres of Sunshine" to sun-enthused tourists, even

though about 3,500 acres of the property was still under water.

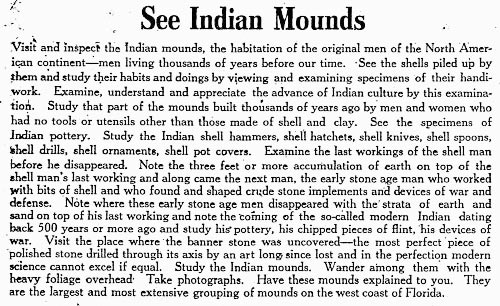

It was to be the "Florida Riviera." In 1923, hoping to

increase its value, he planted Indian artifacts on his Riviera

and summoned J. Walter Fewkes of the Smithsonian Institute.

Finding the relics made the property a key archeological find.

After the bridge's 1924 opening, Elliott enjoyed relaxing and

drinking with the boys, and making light of his Weedon Island

scam. It didn't help his Riviera, which fell victim to

Florida's economic bust in 1926. Read about Elliott's

downfall from the link under his photo.

Later, convinced it was not

such a bad idea, he established the "Boulevard and Bay Land

Development Company" and scooped up some choice acreage

along the bridge approaches on Weedon Island. He offered "Five

Thousand Acres of Sunshine" to sun-enthused tourists, even

though about 3,500 acres of the property was still under water.

It was to be the "Florida Riviera." In 1923, hoping to

increase its value, he planted Indian artifacts on his Riviera

and summoned J. Walter Fewkes of the Smithsonian Institute.

Finding the relics made the property a key archeological find.

After the bridge's 1924 opening, Elliott enjoyed relaxing and

drinking with the boys, and making light of his Weedon Island

scam. It didn't help his Riviera, which fell victim to

Florida's economic bust in 1926. Read about Elliott's

downfall from the link under his photo.

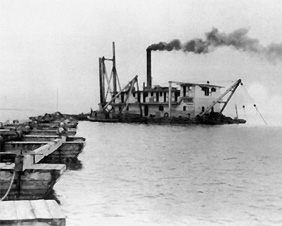

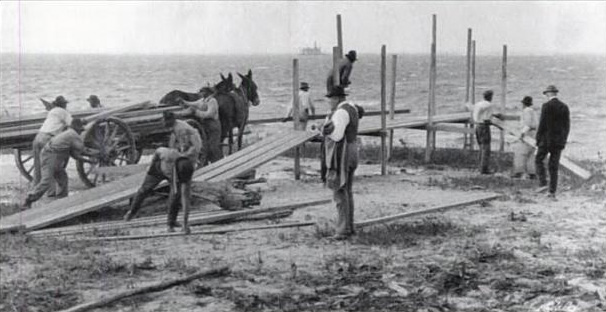

a causeway ten

feet above the mean low-water level. This was about a foot above

the maximum height of the bay's storm surge during the great

hurricane of October, 1921. The causeway from the Tampa

side is three-quarters of a mile long, and the one from the St.

Petersburg side is approximately two and a half miles long.

According to one estimate, causeway construction is about five

times less expensive than bridge construction.

a causeway ten

feet above the mean low-water level. This was about a foot above

the maximum height of the bay's storm surge during the great

hurricane of October, 1921. The causeway from the Tampa

side is three-quarters of a mile long, and the one from the St.

Petersburg side is approximately two and a half miles long.

According to one estimate, causeway construction is about five

times less expensive than bridge construction.

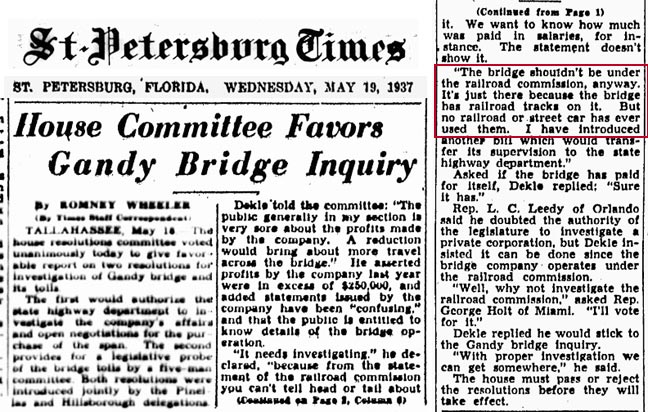

May 19, 1937 article "House

Committee Favors Gandy Bridge Inquiry"

May 19, 1937 article "House

Committee Favors Gandy Bridge Inquiry"