|

Blanche Armwood |

|

|

|

Blanche Armwood was a Tampa native and the first African-American woman from Florida to graduate from an accredited law school, Howard University. Armwood High School in Seffner, which opened in 1984, was named after her.

"What you are is God’s gift to you; what you make of yourself is your gift to God" reads the inscription at the front of the Armwood family scrapbook. This poetic concept aptly describes the character of Blanche Armwood. An early 20th-century Renaissance woman, Ms. Armwood steadfastly held the values of hard work, religious morality, and judicial equality before the American consciousness. She used diplomacy to present these ideals to the American public. Called a "Female Booker T. Washington," Armwood served as liaison between the black and white races. She was administrator, educator, innovator, writer, and poet. |

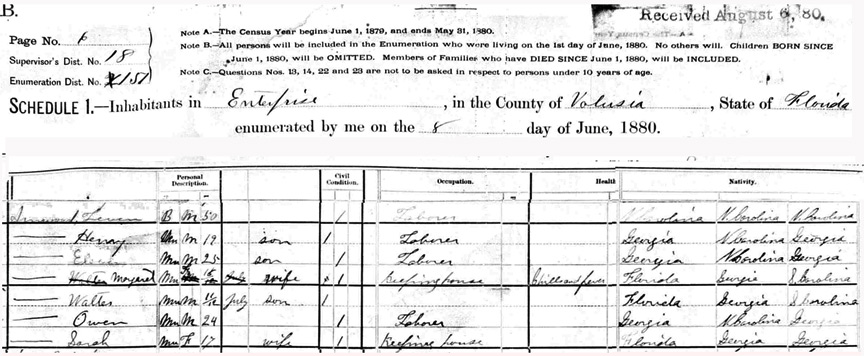

| Born in Tampa on Jan. 23, 1890, Blanche was the youngest of five children.

Her father, Levin Armwood, Jr. was born in 1855 to slave parents in Colquitt,

Georgia. Blanche's grandfather, Levin Armwood, Sr. moved his famiy to

Enterprise, Volusia County after emancipation, arriving as a boy by wagon train from Georgia in

1866 where by 1880, they lived in Volusia County. Blanche's great uncle, John Armwood, had been a negotiator between

the Seminoles and white settlers on the southern Florida Frontier, and

early landowner when he homesteaded 159 acres in early Hillsborough

County in 1890.

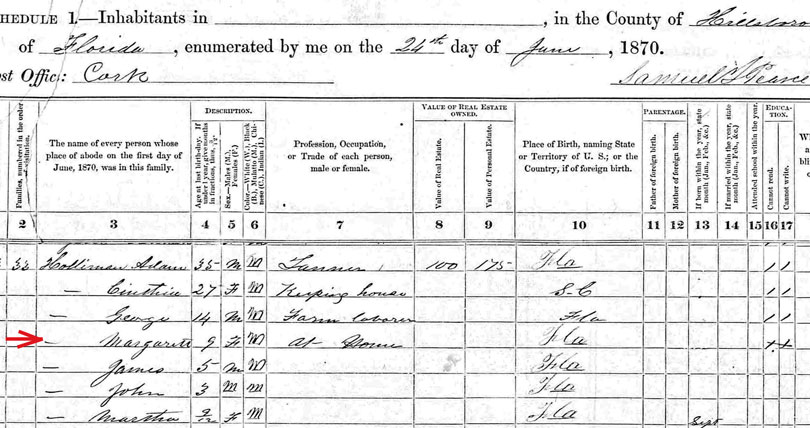

By the mid 1880s, the Armwoods moved to Tampa. They lived in Precinct 1, which in the early 1900s was their home on Constant Street until 1911. In late 1911 or 1912, Levin Armwood, Jr. moved to the home in Seffner where the family reunion photo below was taken. Blanche's mother, Margaret Holloman, was one of 12 children. Margaret's father, Adam Holloman (b.1838 d. 1905), owned citrus groves and was Hillsborough County commissioner from 1873 to 1877. Margaret's grandfather, Mills Holloman (b.1895 d. 1882) was also a citrus grower who served as Hillsborough County commissioner, from 1868 to 1871.

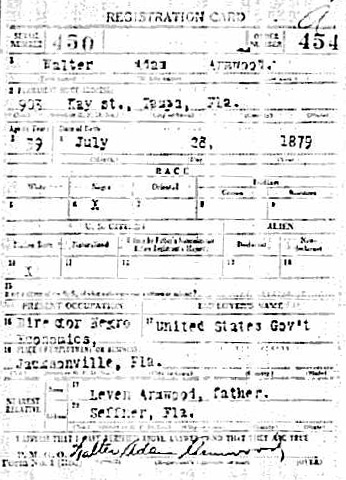

Levin Armwood, Jr. and Margaret "Maggie" Holloman married in 1878. Together, Levin and Margaret raised a family which extolled traditional Christian values of hard work, thrift, and love of God. With the aid of his father-in-law and perhaps some assistance from the Freedmen's Bureau, Levin Armwood, Jr. also became a citrus grower. A trusted member of the community and pastor in his church, Levin Armwood, Jr. was Tampa’s first black police officer as a deputy sheriff and Supervisor of County Roads constructed by prisoners. Margaret earned extra money as a dressmaker. Three children, Walter, Idella, and Blanche survived to adulthood. All became model citizens. Walter, an architect, became professor at Bethune-Cookman College and principal of Brewer Normal School in South Carolina. He and his father jointly owned "The Gem", which was for many years Tampa's only black-owned drugstore. During WW1, Walter was Florida State Supervisor for the U.S. Bureau of Negro Economics. Idella, a licensed businesswoman in 1910, was a shopkeeper, Home Economics teacher in Hillsborough County, officer in the Lilly White Society, and remained active in women’s clubs and community activities.

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

Armwood family reunion at the home of Levin Armwood, Jr. in Seffner, Dec. 25, 1912

Photo from Exploring Florida, Courtesy of the Special Collections

Department, University of South Florida. Digitization provided by the

USF Libraries Digitization Center.

Place your cursor on the image to see persons identified.

Special thanks to Levin G. Armwood, P.E., a grandson of Walter and

Hattie V. Armwood, for providing identification of persons in this

photo, unless otherwise noted below. 1Identification of Maggie Holloman Armwood is based solely on a comparison of appearance to the lady identified as Maggie in the circa 1920s photo seen later in this feature. 2The infant in the arms of Hattie V. Armwood identified as John H. Armwood, Sr. could be Levin Armwood (III), depending on the accuracy of the photo date, which was provided by John H. Armwood, Jr. According to the 1920 census of Walter and Hattie Armwood, their son Walter Jr. was born in 1908, their son Levin was born in 1910, and their son John was born in 1912. It is estimated that Walter, Jr. here appears to be around 4 years old, placing the year of the photo as 1912, thus leading to the conclusion that the infant is John.

By Levin G. Armwood, P.E.

I don't know if

this house in Seffner is still standing. My uncle Henry P. Armwood Sr.

said he had visited it in the eighties and it was still there except the

front porch was screened in. He also discussed the photo with me, but he

wasn't born at the time it was taken. Walter Adam Armwood, my grandfather, who was among other things,

a dean at Florida A&M and president of Brewer college in South Carolina and

during WWI, was the Director of Negro Economics for the State of Florida.

As the director, he traveled the state working to resolve race problems,

often caused by the KKK, that might slow the war effort.

|

|

|

|

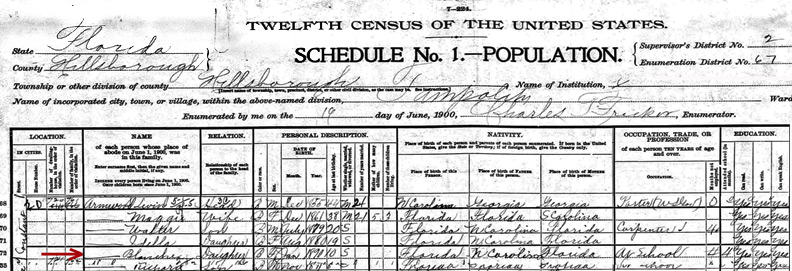

1900 Census,

Hillsborough County, Tampa, the Armwood family at 20 Constance Street

& Governor Street |

| Blanche grew up in a loving home with parents who provided her with the best

education possible for a black female in the late nineteenth and early twentieth

century South. As community focal points, the church and school provided

Blanche with her earliest opportunities to exercise leadership ability. She

developed oratory skills and sang in the church choir. Although they were

not Catholic, rather than registering their daughter at one of Tampa’s poor,

segregated, black public schools, the Armwoods enrolled Blanche in Saint Peter

Claver, an excellent school available to black children. Blanche graduated

in 1902 with highest honors. That same year, at age 12, Blanche also

passed the Florida State Uniform Teachers Examination.

Because Tampa did not have a black high school, the Armwoods then sent twelve-year-old Blanche to Spelman Seminary (later Spelman College) in Atlanta, Georgia. Four years later, in 1906, she graduated from the English-Latin course "summa cum laude", merited a teaching certificate. She had planned to attend college, however, because of her father’s poor health, Blanche returned to Tampa instead; that fall she started teaching in the city’s black public school system. |

|

|

|

Blanche Armwood at 16, upon graduation from Spelman Seminary in Atlanta |

| Although the black community into which Blanche was born was largely self-contained, blacks held responsible leadership positions and owned city and county real estate. Blacks established businesses, schools, and churches. According to Hazel Orsley, cousin of Blanche Armwood, it was not until the 1920s, when the Tampa area population began to boom, that racism became a major problem. In 1913, following a whirlwind love affair, Blanche suspended her teaching career, married attorney Daniel Webster Perkins, and moved to "The Roost" in Knoxville, Tennessee. However, her moral convictions doomed the marriage to failure. Frequently a small boy and his mother would stand near the entrance to the Perkins’ Knoxville home. When Blanche discovered that the boy was her husband’s illegitimate son, she had the marriage annulled.

|

|

|

|

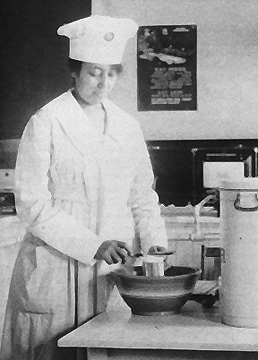

Armwood’s public career began in 1914 when she returned to Tampa and the

Tampa Gas Company, in conjunction with the Hillsborough County Board of

Education and the Colored Ministers Alliance, hired her to organize an

industrial arts school that would specialize in domestic science. As more homes

began cooking with gas instead of wood stoves, there was a need to educate

women in the use of gas appliances. Blanche started The Tampa

School of Household Arts and trained black women and girls to use modern appliances

and taught techniques that would enable them to properly perform their duties as

domestic servants. Under the direction of the former teacher, the school was an

enormous success. In its first year of operation, over two hundred women

received certificates of completion. From there, Armwood went on to set up

similar institutions in Roanoke, Virginia; Rock Hill, South Carolina; Athens,

Georgia; and New Orleans, Louisiana. Blanche Armwood Perkins, creator of the Tampa School of Household Arts, Hillsborough County Schools, circa 1915 |

| Blanche moved to New Orleans for much of 1917 to 1920, where Blanche gained state and federal sanction for her supervisor of home demonstration work. There she published a 37 page wartime cookbook "Food Conservation in the Home" in 1918, which was popular with women of all races, and could be found in most every Tampa home. The introduction extols patriotism: "Unless the individual American home, the unit of the Nation’s strength, will pledge itself to strict economy and conservation, there is imminent danger of defeat for the Nation because of famine in the ranks of our Allies. We will use corn, rye, barley, oats, potatoes and other wheat substitutes while we enjoy the comfort of our homes and save the wheat for the valiant fighters in France. Every pound of white flour saved is equal to a bullet in our Nation’s defense." |

|

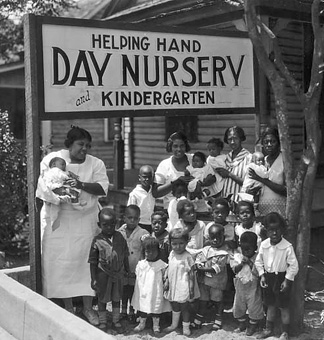

Meanwhile Blanche married Dr. John C. Beatty, a dentist, and moved to Alexandria, LA, in February 1919. Dr. Beatty was a graduate of Howard University Dental College, and had practiced dentistry for several years. John supported Blanche’s career and relocated his practice to Tampa in 1922. Aware of Blanche Beatty’s reputation as speaker and organizer, Jesse Thomas, southern field director of the National Urban League, encouraged her to become the first Executive Secretary of the Tampa Urban League, a social welfare organization designed to help African-Americans adjust to urban life. Under Armwood’s leadership, the TUL provided the city’s black inhabitants with some of the institutions and services that it lacked as a result of segregation. The organization, for example, was instrumental in setting up the Booker T. Washington Branch of the Tampa Chapter of the American Red Cross and the Helping Hand Day Nursery and Kindergarten. Blanche Armwood Beatty (kneeling at right) with members of the Tampa Urban League in 1925. Seated in the middle is Clara Alston.

|

|

|

|

|

|

In 1922, the

Hillsborough County School Board appointed Armwood the first Supervisor of

Negro Schools as well. At the time, the children could only attend six

months a year. During her eight-year tenure, she secured five new school

buildings, increased black teachers’ salaries, and extended the school

year for black students from six to nine months. Faced with inferior

schools and scant supplies, the highlight of her term came in 1926 when

Booker T. Washington High School opened its doors to African-American

youths in Tampa. Four years later, it became the first accredited black

high school in the county. Aside from the leadership positions she held in Tampa, Armwood was heavily involved in two major African-American organizations. She was chair of the Home Economics Department for the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) and State Organizer of the Louisiana Chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Armwood also participated in the suffrage movement, the anti-lynching crusades, and the 1920 presidential election as a national campaign speaker for the Republican Party. However important these accomplishments were, for Armwood they were not enough.

|

|

Blanche had outspoken opinions on the role of women in society. She fought the opposers of women’s suffrage "tongue in cheek" claiming "Our sympathies go out to the opposer of the woman in politics, however, since we realize the apparent unfairness of the arrangement by which each woman is allowed two votes: her own and that of the man whose action she governs.” A woman should be a "lady"-- dependable and reliable, and above all, demand respect. She achieved this by being well groomed and gracious, by keeping a tidy house and preparing nutritious meals; by exercising her intelligence. It was the responsibility of women to uphold society's morals. With this in mind, Blanche was appalled by the moral atrocities committed by the 1920s flappers. She writes, "Alas too many of our women and girls wear costumes that are positively indecent, inviting insult and improper advances from the masculine sex, then criticizing the weakling that they themselves have created; calling attention to the baser part of our natures as we walk the streets, instead of demanding respect and admiration by the utter seclusion of our animal natures and the presentation of the nobility, the personality, the 'God in us', as did the woman of former ages, who walked head and shoulders erect and chests prominent to show that they were somebody .... Are we returning to barbarism?” |

||

|

Armwood family,1920s

Front, L to R: Blanche's parents, Levin Armwood, Jr. and Margaret "Maggie" Holloman Armwood; Blanche's brother, Walter Adam Armwood. Back row: Blanche's brother-in-law and sister, James Street & Idella Armwood Street; Blanche Armwood Beatty and her husband, Dr. John Beatty Photo identification from the Sunland Tribune, Vol. XV, Nov. 1989, Tampa Historical Society |

|

| In the late twenties tragedy struck when John Beatty was shot and killed during a struggle with the family chauffeur. Details surrounding the killing were sketchy, but it was finally ruled accidental. This brought a period of devastation and ill health to Blanche. She became involved in church work, where she met Edward T. Washington, a maintenance supervisor, for the Interstate Commerce Commission. The two were married in 1931 and moved to Washington, D.C. | |

It

is believed that all the Armwoods are related and I believe they

originated in Maryland in the 1700s. The group photo is arranged

around my great great grandfather, Levin Armwood I. He is the bearded

man. He really is as tall as he looked; they say he was around six foot

six or eight. The old men or either side and slightly in front of him

are his sons. [Marked in yellow, Owen and Levin, Jr., with other two

sons Lewis and Henry] The younger men in front of them are from the

next generation. Their children are in the front.

It

is believed that all the Armwoods are related and I believe they

originated in Maryland in the 1700s. The group photo is arranged

around my great great grandfather, Levin Armwood I. He is the bearded

man. He really is as tall as he looked; they say he was around six foot

six or eight. The old men or either side and slightly in front of him

are his sons. [Marked in yellow, Owen and Levin, Jr., with other two

sons Lewis and Henry] The younger men in front of them are from the

next generation. Their children are in the front.